During the first half of this project, we were incredibly interested in analyzing the different ways in which death functions as a theme within the sunday school books. Through our creation of an Omeka site, we were able to dive into the texts on a literary level, comparing and contrasting the books of our dataset with specific secular works of the time. (If you are interested in exploring our Omeka site click here) In order to bring our project full circle, we decided to conduct a second textual analysis, further exploring what words and phrases surrounded the word “death” in each book.

However, the decision to explore death a second time was not purely based on the desire to finish where we started. We also wanted to expand and build upon the work conducted for our previous website. Rather than focusing on the literature itself, this textual analysis has given us a metadata-focused perspective on how the theme works throughout the collection. The metadata, or data about data, has allowed us to identify patterns and connections that we were unable to see previously when simply looking at how death functions on a literary level.

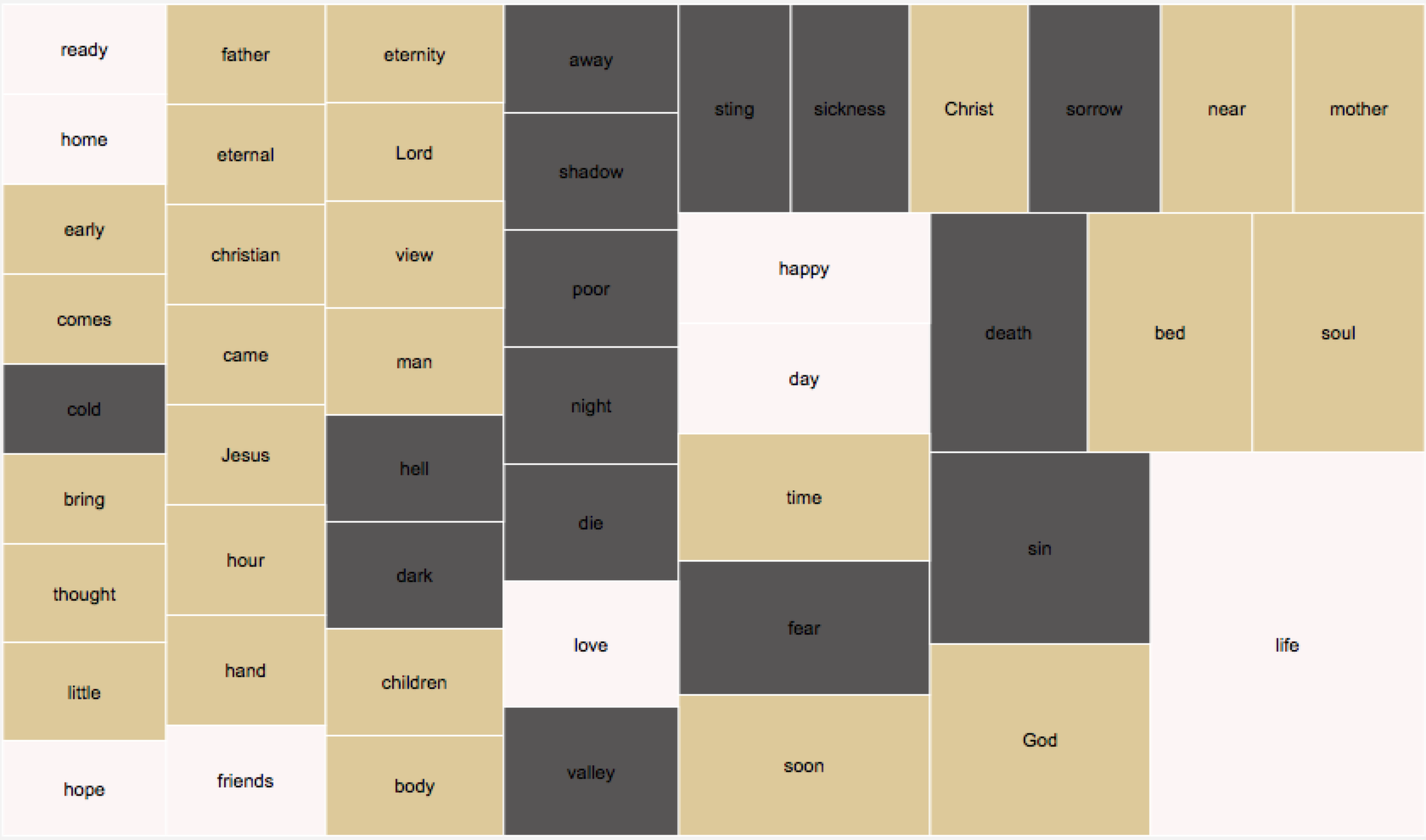

In order to emphasize our findings, we have provided two graphs:

Click on the graphical representation and zoom in to view specific words more clearly.

The first is a hierarchal tree graph depicting the top fifty words that surround the word “death”. The bigger the box, the more frequent the word. In addition to hierarchy, we also use this graph to denote what types of words surround death by the color of the box.

Words denoted by the beige color are considered neutral words. This was determined because they have the possibility of being presented with either a negative or positive connotation, depending on the context in which these words are used. Both God and Jesus were included in the neutral words because, in the event of Jesus’ crucifixion, the discussion could be focused negatively. Meanwhile, in the event of his resurrection, the discussion could be focused positively. The same is true of God. All of these words represent consistencies in theology, as they allude to discussions of the soul, body, and eternity. They also suggest recurrences of specific themes such as deathbed scenes and untimely deaths of children.

White represents words that suggest a positive connotation of death. This type of connotation is defined as anything that strives to bring to light the idea of eternal life through hope of heaven, as remarked in John 3:16: “For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life”. The positive words depicted in this visualization include: ready, home, hope, life, friends, love, day, and happy. Each of these words emphasize a certain readiness and acceptance of death as a result of the hope it brings. The word friends, in particular, is included in collection because they are emphasized in a manner of the dying being surrounded, supported, and loved by their close acquaintances. While smaller in number when compared to the other types of words, each of these words represent the presence of positive messages that surround the darkness of mortality.

While surrounded by light, this darkness is still incredibly prevalent throughout our collection and is depicted in the graph by the words highlighted in black. Each of these words represent a negative connotation of death. This is defined as anything that suggests suffering or any form of damnation. These words include sin, death, sorrow, fear, sickness, sting, away, shadow, poor, night, die, valley, hell, dark, cold. The word death itself is included in this graph because it often occurs multiple times in a row in one phrase. Words such as fear, sting, shadow, and valley all suggest a recurrence of specific phrases in the bible such as Psalm 23:4: “Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil.” and 1 Corinthians 15:55: “Where, O death, is your victory? Where, O death, is your sting?” It is important to consider the context in which these words are used, both in the bible and in the sunday school books. While they suggest death’s pain and suffering, they are always surrounded by words that contradict their darkness. Both in the bible and in the sunday school books, the acknowledgement of this darkness is overshadowed by the salvation of Christ.

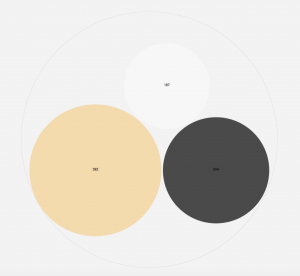

This gives new meaning to the unequal distribution of positive and negative words. This distribution is emphasized through the second graph, which indicates the sheer volume of positive, negative, and neutral words:

Click on the graphical representation and zoom in to view it more clearly.

The same colors from the first graph are also applied here, and it is necessary because it further comments on the uneven balance between positive and negative words.

It is curious that the most frequent word is life. Bringing with it a positive connotation in death, it stands out above the rest, occurring 71 times in surrounding phrases whenever death is mentioned, 42 more times than the next word. While, as the second graph shows, negative words occurred much more often than positive words, it is impossible to ignore the sheer volume of instances in which death is discussed within the context of the coming of life. Furthermore, it is important to remember that most negative words are used in an overall positive context. These words are present in order to acknowledge the darkness that will ultimately be overcome by the light of God through Jesus’ death on the cross. So despite the overabundance of negative words and despite the fear of eternal damnation and suffering, the most frequent message is that there is life within death, and that all of the suffering is ultimately overcome by salvation.

Concluding our research by returning our focus to death has done much more than bring our project full circle. It has allowed us to look at the entirety of our dataset in a new and refreshing way while also building upon previous work. While morbid, our first and final topic of study has given us a fuller understanding of how children of the nineteenth century were taught about the topic of life itself. There is incredible power behind the words of our collection. This power was used in many ways, but the most prominent voice was that of warning: live a good, a God-fearing life, for sickness and darkness are inevitable. In death, life is made sacred. But while death is inevitable, hell is not. “Though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil” (Psalms 23:4). Our dataset exists in order to provide a religious education for children in a time when that was the only instruction many children received. Our research has further explored and emphasized the ways in which this primitive education sculpted the young minds of the nineteenth century, morbidly and bluntly discussing the passing of life while ultimately pointing towards the hope of salvation.